Shiva

| Shiva | |

|---|---|

A statue depicting Shiva meditating |

|

| Devanagari | शिव |

| Sanskrit Transliteration | Śiva |

| Affiliation | Deva (Trimurti) |

| Abode | Mount Kailāsa[1] |

| Mantra | Aum Namah Sivaya |

| Weapon | Trident (Trishula) |

| Consort | Sati, Parvati, Kali, Durga, Chandi |

| Mount | Nandi (bull) |

Shiva (pronounced /ˈʃiːvə/; Sanskrit: शिव Śiva, meaning "auspicious one";) is a major Hindu deity, and the Destroyer or transformer of the Trimurti, the Hindu Trinity of the primary aspects of the divine.[2] In the Shaiva tradition of Hinduism, Shiva is seen as the Supreme God. In the Smarta tradition, he is regarded as one of the five primary forms of God.[3]

Followers of Hinduism who focus their worship upon Shiva are called Shaivites or Shaivas (Sanskrit Śaiva).[4] Shaivism, along with Vaiṣṇava traditions that focus on Vishnu and Śākta traditions that focus on the goddess Shakti are three of the most influential denominations in Hinduism.[3]

Shiva is usually worshipped in the abstract form of Shiva linga. In images, he is generally represented as immersed in deep meditation or dancing the Tandava upon Apasmara Purusha, the demon of ignorance in his manifestation of Nataraja, the lord of the dance.

Contents |

Etymology and other names

The Sanskrit word Shiva (Devanagari: शिव, śiva) is an adjective meaning "auspicious, kind, gracious".[5][6] As a proper name it means "The Auspicious One", used as a name for Rudra.[6] In simple English transliteration it is written either as Shiva or Siva. The adjective śiva, meaning "auspicious", is used as an attributive epithet not particularly of Rudra, but of several other Vedic deities.[7]

The Sanskrit word śaiva means "relating to the god Shiva", and this term is the Sanskrit name both for one of the principal sects of Hinduism and for a member of that sect.[8] It is used as an adjective to characterize certain beliefs and practices, such as Shaivism.[9]

Adi Sankara, in his interpretation of the name Shiva, the 27th and 600th name of Vishnu sahasranama, the thousand names of Vishnu interprets Shiva to have multiple meanings: "The Pure One", or "the One who is not affected by three Gunas of Prakrti (Sattva, Rajas, and Tamas)" or "the One who purifies everyone by the very utterance of His name."[10] Swami Chinmayananda, in his translation of Vishnu sahasranama, further elaborates on that verse: Shiva means "the One who is eternally pure" or "the One who can never have any contamination of the imperfection of Rajas and Tamas".[11]

Shiva's role as the primary deity of Shaivism is reflected in his epithets Mahādeva ("Great God"; mahā = Great + deva = God),[12][13] Maheśhvara ("Great Lord"; mahā = Great + īśhvara = Lord),[14][15] and Parameśhvara ("Supreme Lord").[16]

There are at least eight different versions of the Shiva Sahasranama, devotional hymns (stotras) listing many names of Shiva.[17] The version appearing in Book 13 (Anuśāsanaparvan) of the Mahabharata is considered the kernel of this tradition.[18] Shiva also has Dasha-Sahasranamas (10,000 names) that are found in the Mahanyasa. The Shri Rudram Chamakam, also known as the Śatarudriya, is a devotional hymn to Shiva hailing him by many names.[19][20]

Historical development

The worship of Shiva is a pan-Hindu tradition, practiced widely across all of India, Nepal and Sri Lanka.[21][22] Some historians believe that the figure of Shiva as we know him today was built up over time, with the ideas of many regional sects being amalgamated into a single figure.[23] How the persona of Shiva converged as a composite deity is not well documented.[24] Axel Michaels explains the composite nature of Shaivism as follows:

Like Vişņu, Śiva is also a high god, who gives his name to a collection of theistic trends and sects: Śaivism. Like Vaişņavism, the term also implies a unity which cannot be clearly found either in religious practice or in philosophical and esoteric doctrine. Furthermore, practice and doctrine must be kept separate.[25]

An example of assimilation took place in Maharashtra, where a regional deity named Khandoba is a patron deity of farming and herding castes.[26] The foremost center of worship of Khandoba in Maharashtra is in Jejuri.[27] Khandoba has been assimilated as a form of Shiva himself,[28] in which case he is worshipped in the form of a lingam.[26][29] Khandoba's varied associations also include an identification with Surya [26] and Karttikeya.[30]

The Pashupati seal

A seal discovered during the excavation of Mohenjo-daro has drawn attention as a possible representation of a "proto-Shiva" figure.[31] This Pashupati (Lord of animal-like beings)[32] seal shows a seated figure, possibly ithyphallic, surrounded by animals.[33] Sir John Marshall and others have claimed that this figure is a prototype of Shiva and have described the figure as having three faces seated in a "yoga posture" with the knees out and feet joined. However, this claim is not without its share of critics, with some academics like Gavin Flood[31][34] and John Keay characterizing them as unfounded.[35]

Rudra

Shiva as we know him today shares many features with the Vedic god Rudra,[36] and both Shiva and Rudra are viewed as the same personality in a number of Hindu traditions. Rudra, the god of the roaring storm, is usually portrayed in accordance with the element he represents as a fierce, destructive deity.

The oldest surviving text of Hinduism is the Rig Veda, which is dated to between 1700 and 1100 BCE based on linguistic and philological evidence.[37] A god named Rudra is mentioned in the Rig Veda. The name Rudra is still used as a name for Shiva. In RV 2.33, he is described as the "Father of the Maruts", a group of storm gods.[38] Furthermore, the Rudram, one of the most sacred hymns of Hinduism found both in the Rig and the Yajur Vedas and addressed to Rudra, invokes him as Shiva in several instances, but the term Shiva is used as a epithet for Indra, Mitra and Agni many times.

The identification of Shiva with the older god Rudra is not universally accepted, as Axel Michaels explains:

To what extent Śiva's origins are in fact to be sought in Rudra is extremely unclear. The tendency to consider Śiva an ancient god is based on this identification, even though the facts that justify such a far-reaching assumption are meager.[39]

Rudra is called "The Archer" (Sanskrit: Śarva),[40] and the arrow is an essential attribute of Rudra.[41] This name appears in the Shiva Sahasranama, and R. K. Sharma notes that it is used as a name of Shiva often in later languages.[42] The word is derived from the Sanskrit root śarv-, which means "to injure" or "to kill",[43] and Sharma uses that general sense in his interpretive translation of the name Śarva as "One who can kill the forces of darkness".[42] The names Dhanvin ("Bowman")[44] and Bāṇahasta ("Archer", literally "Armed with arrows in his hands")[44][45] also refer to archery.

Identification with Vedic deities

Shiva's rise to a major position in the pantheon was facilitated by his identification with a host of Vedic deities, including Agni, Indra, Prajāpati, Vāyu, and others.[46]

Agni

Rudra and Agni have a close relationship.[47][48] The identification between Agni and Rudra in the Vedic literature was an important factor in the process of Rudra's gradual development into the later character as Rudra-Shiva.[49] The identification of Agni with Rudra is explicitly noted in the Nirukta, an important early text on etymology, which says, "Agni is called Rudra also."[50] The interconnections between the two deities are complex, and according to Stella Kramrisch:

The fire myth of Rudra-Śiva plays on the whole gamut of fire, valuing all its potentialities and phases, from conflagration to illumination.[51]

In the Śatarudrīa, some epithets of Rudra, such as Sasipañjara ("Of golden red hue as of flame") and Tivaṣīmati ("Flaming bright"), suggest a fusing of the two deities.[52] Agni is said to be a bull,[53] and Lord Shiva possesses a bull as his vehicle, Nandi. The horns of Agni, who is sometimes characterized as a bull, are mentioned.[54][55] In medieval sculpture, both Agni and the form of Shiva known as Bhairava have flaming hair as a special feature.[56]

Indra

According to a theory, the Puranic Shiva is a continuation of the Vedic Indra.[57] He gives several reasons for his hypothesis. Both Shiva and Indra are known for having a thirst for Soma. Both are associated with mountains, rivers, male fertility, fierceness, fearlessness, warfare, transgression of established mores, the Aum sound, the Supreme Self. In the Rig Veda the term śiva is used to refer to Indra. (2.20.3,[58] 6.45.17,[59][60] and 8.93.3.[61]) Indra, like Shiva, is likened to a bull.[62][63] In the Rig Veda, Rudra is the father of the Maruts, but he is never associated with their warlike exploits as is Indra.[64]

Attributes

- Shiva's Form:

Lord Siva wears a deer in the left upper hand. He has Trident in the right lower arm. He has fire and Damaru and Malu or a kind of weapon. He wears five serpents as ornaments. He wears a garland of skulls. He is pressing with His feet the demon Muyalaka, a dwarf holding a cobra. He faces south. Panchakshara itself is His body.

- Third eye: Shiva is often depicted with a third eye, with which he burned Desire (Kāma) to ashes.[65] There has been no controversy regarding the original meaning of Shiva's name, it is a combination of two name shiv, where(I from shiv) means shakti(spouse) if it is removed from the name shiv,remain left is shav(Deadbody).That means shav and shakti together makes it shiv(Ardhanareshwar). Tryambakam (Sanskrit: त्र्यम्बकम्), which occurs in many scriptural sources.[66] In classical Sanskrit, the word ambaka denotes "an eye", and in the Mahabharata, Shiva is depicted as three-eyed, so this name is sometimes translated as "having three eyes".[67] However, in Vedic Sanskrit, the word ambā or ambikā means "mother", and this early meaning of the word is the basis for the translation "having three mothers" that was used by Max Müller and Arthur Macdonell.[68][69] Since no story is known in which Shiva had three mothers, E. Washburn Hopkins suggested that the name refers not to three mothers, but to three mother-goddesses who are collectively called the Ambikās.[70] Other related translations have been "having three wives or sisters" or were based on the idea that the name actually refers to the oblations given to Rudra, which according to some traditions were shared with the goddess Ambikā.[71]

- Crescent moon: Shiva bears on his head the crescent moon.[72] The epithet Chandraśekhara (Sanskrit: चन्द्रशेखर "Having the moon as his crest" - chandra = "moon", śekhara = "crest, crown")[73][74][75] refers to this feature. The placement of the moon on his head as a standard iconographic feature dates to the period when Rudra rose to prominence and became the major deity Rudra-Shiva.[76] The origin of this linkage may be due to the identification of the moon with Soma, and there is a hymn in the Rig Veda where Soma and Rudra are jointly emplored, and in later literature, Soma and Rudra came to be identified with one another, as were Soma and the moon.[77]

The crescent moon is shown on the side of the Lord's head as an ornament. The waxing and waning phenomenon of the moon symbolizes the time cycle through which creation evolves from the beginning to the end. Since the Lord is the Eternal Reality, He is beyond time. Thus, the crescent moon is only one of His ornaments.The wearing of the crescent moon in His head indicates that He has controlled the mind perfectly.

- Ashes: Shiva smears his body with ashes (bhasma).[78] Some forms of Shiva, such as Bhairava, are associated with a very old Indian tradition of cremation-ground asceticism that was practiced by some groups who were outside the fold of brahmanic orthodoxy.[79] These practices associated with cremation grounds are also mentioned in the Pali canon of Theravada Buddhism.[80] One epithet for Shiva is "inhabitant of the cremation ground" (Sanskrit: śmaśānavāsin, also spelled Shmashanavasin), referring to this connection.[81]

- Matted hair: Shiva's distinctive hair style is noted in the epithets Jaṭin, "the one with matted hair",[82] and Kapardin, "endowed with matted hair"[83] or "wearing his hair wound in a braid in a shell-like (kaparda) fashion".[84] A kaparda is a cowrie shell, or a braid of hair in the form of a shell, or, more generally, hair that is shaggy or curly.[85]

- Blue throat: The epithet Nīlakaṇtha (Sanskrit नीलकण्ठ; nīla = "blue", kaṇtha = "throat")[86][87] refers to a story in which Shiva drank the poison churned up from the world ocean.[88][89] (See Halāhala.) The Hari Vanśa Purana, on the other hand, attributes the colour of Shiva's throat to an episode in which Vishnu compels Shiva to fly after taking him by the throat and nearly strangling him.[90]

- Sacred Ganga: The Ganga river flows from the matted hair of Shiva. The epithet Gaṅgādhara ("bearer of the river Gaṅgā") refers to this feature.[91][92] The Ganga (Ganges), one of the major rivers of the country, is said to have made her abode in Shiva's hair.[93]The flow of the Ganga also represents the nectar of immortality.

- Tiger skin: He is often shown seated upon a tiger skin,[78] an honour reserved for the most accomplished of Hindu ascetics, the Brahmarishis.[94]Tiger represents lust. His sitting on the tiger’s skin indicates that He has conquered lust.

- Serpents: Shiva is often shown garlanded with a snake.[95]His wearing of serpents on the neck denotes wisdom and eternity.

- Deer:His holding deer on one hand indicates that He has removed the Chanchalata (tossing) of the mind. Deer jumps from one place to another swiftly. The mind also jumps from one object to another.

- Trident: (Sanskrit: Trishula): Shiva's particular weapon is the trident.[78]His Trisul that is held in His right hand represents the three Gunas—Sattva, Rajas and Tamas. That is the emblem of sovereignty. He rules the world through these three Gunas. The Damaru in His left hand represents the Sabda Brahman. It represents OM from which all languages are formed. It is He who formed the Sanskrit language out of the Damaru sound.

- Drum: A small drum shaped like an hourglass is known as a damaru (Sanskrit: ḍamaru).[96][97] This is one of the attributes of Shiva in his famous dancing representation[98] known as Nataraja. A specific hand gesture (mudra) called ḍamaru-hasta (Sanskrit for "ḍamaru-hand") is used to hold the drum.[99] This drum is particularly used as an emblem by members of the Kāpālika sect.[100]

- Nandī: Nandī, also known as Nandin, is the name of the bull that serves as Shiva's mount (Sanskrit: vāhana).[101][102] Shiva's association with cattle is reflected in his name Paśupati, or Pashupati (Sanskrit: पशुपति), translated by Sharma as "lord of cattle"[103] and by Kramrisch as "lord of animals", who notes that it is particularly used as an epithet of Rudra.[104]Rishabha or the bull represents Dharma Devata. Lord Siva rides on the bull. Bull is His vehicle. This denotes that Lord Siva is the protector of Dharma, is an embodiment of Dharma or righteousness.

- Gaṇa: The Gaṇas (Devanagari: गण) are attendants of Shiva and live in Kailash. They are often referred to as the Boothaganas, or ghostly hosts, on account of their nature. Generally benign, except when their lord is transgressed against, they are often invoked to intercede with the lord on behalf of the devotee. Ganesha was chosen as their leader by Shiva, hence Ganesha's title gaṇa-īśa or gaṇa-pati, "lord of the gaṇas".[105]

- Mount Kailāsa: Mount Kailash in the Himalayas is his traditional abode.[78] In Hindu mythology, Mount Kailāsa is conceived as resembling a Linga, representing the center of the universe.[106]

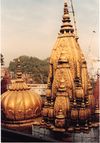

- Varanasi: Varanasi (Benares) is considered as the city specially loved by Shiva, and is one of the holiest places of pilgrimage in India. It is referred to, in religious contexts, as Kashi.[107]

Forms and depictions

According to Gavin Flood, "Śiva is a god of ambiguity and paradox," whose attributes include opposing themes.[108] The ambivalent nature of this deity is apparent in some of his names and the stories told about him.

Destroyer versus benefactor

In the Yajurveda, two contrary sets of attributes for both malignant or terrific (Sanskrit: rudra) and benign or auspicious (Sanskrit: śiva) forms can be found, leading Chakravarti to conclude that "all the basic elements which created the complex Rudra-Śiva sect of later ages are to be found here."[109] In the Mahabharata, Shiva is depicted as "the standard of invincibility, might, and terror", as well as a figure of honor, delight, and brilliance.[110] The duality of Shiva's fearful and auspicious attributes appears in contrasted names.

The name Rudra (Sanskrit: रुद्र) reflects his fearsome aspects. According to traditional etymologies, the Sanskrit name Rudra is derived from the root rud-, which means "to cry, howl".[111] Stella Kramrisch notes a different etymology connected with the adjectival form raudra, which means "wild, of rudra nature", and translates the name Rudra as "the wild one" or "the fierce god".[112] R. K. Sharma follows this alternate etymology and translates the name as "terrible".[113] Hara (Sanskrit: हर) is an important name that occurs three times in the Anushasanaparvan version of the Shiva sahasranama, where it is translated in different ways each time it occurs, following a commentorial tradition of not repeating an interpretation. Sharma translates the three as "one who captivates", "one who consolidates", and "one who destroys."[114] Kramrisch translates it as "the ravisher".[89] Another of Shiva's fearsome forms is as Kāla (Sanskrit: काल), "time", and as Mahākāla (Sanskrit: महाकाल), "great time", which ultimately destroys all things.[115][116][117] Bhairava (Sanskrit: भैरव), "terrible" or "frightful",[118] is a fierce form associated with annihilation.[119]

In contrast, the name Śaṇkara (Sanskrit: शङ्कर), "beneficent"[42] or "conferring happiness"[120] reflects his benign form. This name was adopted by the great Vedanta philosopher Śaṇkara (c. 788-820 CE), who is also known as Shankaracharya.[121][122] The name Śambhu (Sanskrit: शम्भु), "causing happiness", also reflects this benign aspect.[123][124]

Ascetic versus householder

He is depicted as both an ascetic yogin and as a householder, roles which have been traditionally mutually exclusive in Hindu society.[125] When depicted as a yogin, he may be shown sitting and meditating.[126] His epithet Mahāyogin ("the great Yogi: Mahā = "great", Yogin = "one who practices Yoga") refers to his association with yoga.[127] While Vedic religion was conceived mainly in terms of sacrifice, it was during the Epic period that the concepts of tapas, yoga, and asceticism became more important, and the depiction of Shiva as an ascetic sitting in philosophical isolation reflects these later concepts.[128]

As a family man and householder, he has a wife, Parvati (also known as Umā), and two sons, Ganesha and Skanda (also known as Karthikeya and Murugan). His epithet Umāpati ("The husband of Umā") refers to this idea, and Sharma notes that two other variants of this name that mean the same thing, Umākānta and Umādhava, also appear in the sahasranama.[129] Umā in epic literature is known by many names, including the benign Pārvatī.[130][131] She is identified with Devi, the Divine Mother, and with Shakti (divine energy). As a householder, he is known for the great love and respect he has for his consort. Ganesha is worshipped throughout India and Nepal as the Remover of Obstacles, Lord of Beginnings and Lord of Obstacles. Karthikeya is worshipped in Southern India (especially in Tamil Nadu, Kerala and Karnataka) by the names Subrahmanya, Subrahmanyan, Shanmughan, Swaminathan and Murugan, and in Northern India by the names Skanda, Kumara, or Karttikeya.[132] The consorts of Lord Shiva are the source of his creative energy. They represent the dynamic extension of Shiva onto this universe.[133]

Nataraja

The depiction of Shiva as Nataraja (Telugu: నటరాజు, Tamil: நடராஜா, Sanskrit: naṭarāja, "Lord of Dance") is popular.[134][135] The names Nartaka ("dancer") and Nityanarta ("eternal dancer") appear in the Shiva Sahasranama.[136] His association with dance and also with music is prominent in the Puranic period.[137] In addition to the specific iconographic form known as Nataraja, various other types of dancing forms (Sanskrit: nṛtyamūrti) are found in all parts of India, with many well-defined varieties in Tamil Nadu in particular.[138] The two most common forms of the dance are the Tandava, which later came to denote the powerful and masculine dance as Kala-Mahakala associated with the destruction of the world,[139][140] and Lasya, which is graceful and delicate and expresses emotions on a gentle level and is considered the feminine dance attributed to the goddess Parvati.[141][142] Lasya is regarded as the female counterpart of Tandava.[142] The Tandava-Lasya dances are associated with the destruction-creation of the world.[143][144]

Dakshinamurthy

Dakshinamurthy, or Dakṣiṇāmūrti (Telugu : దక్షిణామూర్తి , Sanskrit: दक्षिणामूर्ति),[145] literally describes a form (mūrti) of Shiva facing south (dakṣiṇa). This form represents Shiva in his aspect as a teacher of yoga, music, and wisdom and giving exposition on the shastras.[146] This iconographic form for depicting Shiva in Indian art is mostly from Tamil Nadu.[147] Elements of this motif can include Shiva seated upon a deer-throne and surrounded by sages who are receiving his instruction.[148]

Ardhanarishvara

An iconographic representation of Shiva called (Ardhanārīśvara) shows him with one half of the body as male and the other half as female. According to Ellen Goldberg, the traditional Sanskrit name for this form (Ardhanārīśvara) is best translated as "the lord who is half woman", not as "half-man, half-woman".[149] In Hindu philosophy, this is used to visualize the belief that the sacred ultimate power of the universe as being both feminine and masculine.[133]

Tripurantaka

Lord Shiva is often depicted as an archer in the act of destroying the triple fortresses, Tripura, of the Asuras.[150] Shiva's name Tripurantaka (Sanskrit: त्रिपुरान्तक, Tripurāntaka), "ender of Tripura", refers to this important story.[151]

Lingam

Apart from anthropomorphic images of Shiva, the worship of Shiva in the form of a lingam, or linga, is also important.[36][152][153] These are depicted in various forms. One common form is the shape of a vertical rounded column. Shiva means auspiciousness, and linga means a sign or a symbol. Hence, the Shivalinga is regarded as a "symbol of the great God of the universe who is all-auspiciousness".[154] Shiva also means "one in whom the whole creation sleeps after dissolution".[154] Linga also means the same thing—a place where created objects get dissolved during the disintegration of the created universe. Since, according to Hinduism, it is the same god that creates, sustains and withdraws the universe, the Shivalinga represents symbolically God Himself.[154] Some scholars, such as Monier-Williams and Wendy Doniger, also view linga as a phallic symbol,[155][156] although this interpretation is disputed by others, including Christopher Isherwood,[157] Vivekananda,[158] Swami Sivananda,[159] and S.N. Balagangadhara.[160]

The worship of the Shiva-Linga originated from the famous hymn in the Atharva-Veda Samhitâ sung in praise of the Yupa-Stambha, the sacrificial post. In that hymn, a description is found of the beginningless and endless Stambha or Skambha, and it is shown that the said Skambha is put in place of the eternal Brahman. Just as the Yajna (sacrificial) fire, its smoke, ashes, and flames, the Soma plant, and the ox that used to carry on its back the wood for the Vedic sacrifice gave place to the conceptions of the brightness of Shiva's body, his tawny matted hair, his blue throat, and the riding on the bull of the Shiva, the Yupa-Skambha gave place in time to the Shiva-Linga.[161][162] In the text Linga Purana, the same hymn is expanded in the shape of stories, meant to establish the glory of the great Stambha and the superiority of Shiva as Mahadeva.[162]

Avatars

Shiva, like some other Hindu deities, is said to have several incarnations, known as avatars. Although Puranic scriptures contain occasional references to avatars of Shiva, the idea is not universally accepted in Saivism.[163]

- Adi Shankara, the 8th-century philosopher of non-dualist Vedanta"Advaita Vedanta", was named "Shankara" after Lord Shiva and is considered by some to have been an incarnation of Shiva.[164]

- In the Hanuman Chalisa, Hanuman is identified as the eleventh avatar of Shiva, but this belief is not universal.[165]

- Virabhadra who was born when Shiva grabbed a lock of his matted hair and dashed it to the ground. Virabhadra then destroyed Daksha's yajna (fire sacrifice) and severed his head as per Shiva's instructions.[166]

The five mantras

Five is a sacred number for Shiva.[167] One of his most important mantras has five syllables (namaḥ śivāya).[168]

Shiva's body is said to consist of five mantras, called the pañcabrahmans.[169] As forms of God, each of these have their own names and distinct iconography:[170]

- Sadyojāta

- Vāmadeva

- Aghora

- Tatpuruṣa

- Īsāna

These are represented as the five faces of Shiva and are associated in various texts with the five elements, the five senses, the five organs of perception, and the five organs of action.[171][172] Doctrinal differences and, possibly, errors in transmission, have resulted in some differences between texts in details of how these five forms are linked with various attributes.[173] The overall meaning of these associations is summarized by Stella Kramrisch:

Through these transcendent categories, Śiva, the ultimate reality, becomes the efficient and material cause of all that exists.[174]

According to the Pañcabrahma Upanishad:

One should know all things of the phenomenal world as of a fivefold character, for the reason that the eternal verity of Śiva is of the character of the fivefold Brahman. (Pañcabrahma Upanishad 31)[175]

Relationship to Vishnu

During the Vedic period, both Vishnu and Shiva (as identified with Rudra) played relatively minor roles, but by the time of the Brahmanas (c. 1000-700 BCE), both were gaining ascendance.[176] By the Puranic period, both deities had major sects that competed with one another for devotees.[177] Many stories developed showing different types of relationships between these two important deities.

Sectarian groups each presented their own preferred deity as supreme. Vishnu in his myths "becomes" Shiva.[178] The Vishnu Purana (4th c. CE) shows Vishnu awakening and becoming both Brahmā to create the world and Shiva to destroy it.[179] Shiva also is viewed as a manifestation of Vishnu in the Bhagavata Purana.[180] In Shaivite myths, on the other hand, Shiva comes to the fore and acts independently and alone to create, preserve, and destroy the world.[181] In one Shaivite myth of the origin of the lingam, both Vishnu and Brahmā are revealed as emanations from Shiva's manifestation as a towering pillar of flame.[182] The Śatarudrīya, a Shaivite hymn, says that Shiva is "of the form of Vishnu".[183] Differences in viewpoints between the two sects are apparent in the story of Śarabha (also spelled "Sharabha"), the name of Shiva's incarnation in the composite form of man, bird, and beast. Shiva assumed that unusual form of Sarabheshwara to chastise Vishnu, who in his hybrid form as Narasimha, the man-lion, killed Hiranyakashipu.[184][185] However, Vaishnava followers including Dvaita scholars, such as Vijayindra Tirtha (1539–95) dispute this view of Narasimha based on their reading of Sattvika Puranas and Śruti texts.[186]

Syncretic forces produced stories in which the two deities were shown in cooperative relationships and combined forms. Harihara is the name of a combined deity form of both Vishnu (Hari) and Shiva (Hara).[187] This dual form, which is also called Harirudra, is mentioned in the Mahabharata.[188] An example of a collaboration story is one given to explain Shiva's epithet Mahābaleśvara, "lord of great strength" (Maha = "great", Bala = "strength", Īśvara = "lord"). This name refers to a story in which Rāvaṇa was given a linga as a boon by Shiva on the condition that he carry it always. During his travels, he stopped near the present Deoghar in Jharkhand to purify himself and asked Narada, a devotee of Vishnu in the guise of a Brahmin, to hold the linga for him, but after some time, Narada put it down on the ground and vanished. When Ravana returned, he could not move the linga, and it is said to remain there ever since.[189]

As one story goes, Shiva is enticed by the beauty and charm of Mohini, Vishnu's female avatar, and procreates with her. As a result of this union, Shasta - identified with regional deities Ayyappa and Ayyanar - is born.[190][191] Shiva is also served by Mohini when a bunch of naughty sages were taught a lesson by Shiva.[192][193]

Maha Shivaratri

Maha Shivratri is a festival celebrated every year on the 13th night or the 14th day of the new moon in the Krishna Paksha of the month of Maagha or Phalguna in the Hindu calendar. This festival is of utmost importance to the devotees of Lord Shiva. Mahashivaratri marks the night when Lord Shiva performed the 'Tandava' and it is also believed that Lord Shiva was married to Parvati. On this day the devotees observe fast and offer fruits, flowers and Bael leaves to Shiva Linga.[194]

Temples

There are many Shiva temples in the Indian subcontinent, the Jyotirlinga temples being the most prominent.

Jyotirlinga temples

The holiest Shiva temples are the 12 Jyotirlinga temples. They are,

| Jyotirlinga | Location | |

|---|---|---|

| Somnath | Prabhas Patan, near Veraval, Gujarat | |

| Mallikārjuna |  |

Srisailam, Andhra Pradesh |

| Mahakaleshwar | Ujjain, Madhya Pradesh | |

| Omkareshwar | near Indore, Madhya Pradesh | |

| Kedarnath |  |

Kedarnath, Uttarakhand |

| Bhimashankar |  |

Disputed:

|

| Kashi Vishwanath |  |

Varanasi, Uttar Pradesh |

| Trimbakeshwar |  |

Trimbak, near Nasik, Maharashtra |

| Ramanathaswamy |  |

Rameswaram, Tamil Nadu |

| Grishneshwar |  |

near Ellora, Maharashtra |

| Vaidyanath |  |

Disputed:

|

| Nageshwar | Disputed:

|

|

Manifestations

In South India, five temples of Shiva are held to be particularly important, as being manifestations of him in the five elemental substances:

| Deity | Manifestation | Temple | Location | State |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sri Jambhukeswar | Water | Jambukeshwarar Temple | Thiruvanaikaval | Tamil Nadu |

| Sri Arunachaleswar | Fire | Annamalaiyar Temple | Thiruvannamalai | Tamil Nadu |

| Sri Kalahastheeswara | Air | Srikalahasti temple | Srikalahasti | Andhra Pradesh |

| Sri Ekambareswar | Earth | Ekambareswarar Temple | Kanchipuram | Tamil Nadu |

| Sri Nataraja | Ether | Natarajar Temple | Chidambaram | Tamil Nadu |

Sabha temples

The five sabha temples where Shiva is believed to perform five different style of dances are:

| Sabha | Temple | Location | State |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pon (Gold) Sabha | Natarajar Temple | Chidambaram | Tamil Nadu |

| Velli (Silver) Sabha | Meenakshi Sundareswarar Temple | Madurai | Tamil Nadu |

| Tamira (Copper) Sabha | Nellaiappar Temple | Tirunelveli | Tamil Nadu |

| Rathna (Gem) Sabha | Thiruvalankadu Vadaaranyeswarar Temple | Thiruvalangadu near Arakkonam |

Tamil Nadu |

| Chitira (Picture) Sabha | Kutraleeswar Temple | Coutrallam | Tamil Nadu |

Other famous temples in India

|

|

Famous temples in other countries

- Pashupatinath Temple located on the banks of Bagmati River in the eastern part of Kathmandu, Nepal

- Lake Mansarovar and Mount Kailash in Tibet, a pilgrimage site believed to be the abode of Lord Shiva

- Gosaikunda Lake located in Rasuwa District, Nepal

|

Mount Kailash in Tibet, believed to be the abode of Lord Shiva |

Gosaikunda Lake is believed to have formed by the Trishul of Lord Shiva after he drank the poison Halahala from Samudra manthan and desperately wanted cold water to quench the overwhelming heat of the poison |

See also

Notes

- ↑ For the name Kailāsagirivāsī (Sanskrit कैलासिगिरवासी), "With his abode on Mount Kailāsa", as a name appearing in the Shiva Sahasranama, see: Sharma 1996, p. 281.

- ↑ Zimmer (1972) p. 124.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Flood (1996), p. 17.

- ↑ Tattwananda, p. 45.

- ↑ Apte, p. 919.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Macdonell, p. 314.

- ↑ For use of the term śiva as an epithet for other Vedic deities, see: Chakravarti, p. 28.

- ↑ Apte, p. 927

- ↑ For the definition "Śaivism refers to the traditions which follow the teachings of Śiva (śivaśāna) and which focus on the deity Śiva... " see: Flood (1996), p. 149.

- ↑ Sri Vishnu Sahasranama, Ramakrishna Math edition, pg.47 and pg. 122.

- ↑ Swami Chinmayananda's translation of Vishnu sahasranama, pg. 24, Central Chinmaya Mission Trust.

- ↑ Kramrisch, p. 476.

- ↑ For appearance of the name महादेव in the Shiva Sahasranama see: Sharma 1996, p. 297

- ↑ Kramrisch, p. 477.

- ↑ For appearance of the name महेश्वर in the Shiva Sahasranama see:Sharma 1996, p. 299

- ↑ For Parameśhvara as "Supreme Lord" see: Kramrisch, p. 479.

- ↑ Sharma 1996, p. viii-ix

- ↑ This is the source for the version presented in Chidbhavananda, who refers to it being from the Mahabharata but does not explicitly clairify which of the two Mahabharata versions he is using. See Chidbhavananda, p.5.

- ↑ For an overview of the Śatarudriya see: Kramrisch, pp. 71-74.

- ↑ For complete Sanskrit text, translations, and commentary see: Sivaramamurti (1976).

- ↑ Flood (1996), p. 17

- ↑ Keay, p.xxvii.

- ↑ Keay, p. xxvii.

- ↑ For Shiva as a composite deity whose history is not well-documented, see: Keay, p. 147.

- ↑ Michaels, p. 215.

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 26.2 Courtright, p. 205.

- ↑ For Jejuri as the foremost center of worship see: Mate, p. 162.

- ↑ 'Khandoba: Ursprung, Geschiche und Umvelt von Pastoralem Gotheiten in Maharashtra, Wiesbaden 1976 (German with English Synopsis) pp. 180-98, "Khandoba is a local deity in Maharashtra and been Sanskritised as an incarnation of Shiva."

- ↑ For worship of Khandoba in the form of a lingam and possible identification with Shiva based on that, see: Mate, p. 176.

- ↑ For use of the name Khandoba as a name for Karttikeya in Maharashtra, see: Gupta, Preface, and p. 40.

- ↑ 31.0 31.1 Flood (1996), pp. 28-29.

- ↑ For translation of paśupati as "Lord of Animals" see: Michaels, p. 312.

- ↑ For a drawing of the seal see Figure 1 in: Flood (1996), p. 29.

- ↑ Flood (2003), pp. 204-205.

- ↑ Keay, p. 14.

- ↑ 36.0 36.1 Michaels, p. 216.

- ↑ For dating based on "cumulative evidence" see: Oberlies, p. 158.

- ↑ Doniger, pp. 221-223.

- ↑ Michaels, p. 217.

- ↑ For Śarva as a name of Shiva see: Apte, p. 910.

- ↑ For archer and arrow associations see Kramrisch, Chapter 2, and for the arrow as an "essential attribute" see: Kramrisch, p. 32.

- ↑ 42.0 42.1 42.2 Sharma 1996, p. 306

- ↑ For root śarv- see: Apte, p. 910.

- ↑ 44.0 44.1 Chidbhavananda, p. 33.

- ↑ For translation of Bāṇahasta as "Armed with arrows in his hands") see: Sharma 1996, p. 294.

- ↑ For Shiva being identified with Agni, Indra, Prajāpati, Vāyu, and others see: Chakravarti, p. 70.

- ↑ For general statement of the close relationship, and example shared epithets, see: Sivaramamurti, p. 11.

- ↑ For an overview of the Rudra-Fire complex of ideas, see: Kramrisch, pp. 15-19.

- ↑ For quotation "An important factor in the process of Rudra's growth is his identification with Agni in the Vedic literature and this identification contributed much to the transformation of his character as Rudra-Śiva." see: Chakravarti, p. 17.

- ↑ For translation from Nirukta 10.7, see: Sarup (1927), p. 155.

- ↑ Kramrisch, p. 18.

- ↑ For "Note Agni-Rudra concept fused" in epithets Sasipañjara and Tivaṣīmati see: Sivaramamurti, p. 45.

- ↑ "Rig Veda: Rig-Veda, Book 6: HYMN XLVIII. Agni and Others". Sacred-texts.com. http://www.sacred-texts.com/hin/rigveda/rv06048.htm. Retrieved 2010-06-06.

- ↑ For the parallel between the horns of Agni as bull, and Rudra, see: Chakravarti, p. 89.

- ↑ RV 8.49; 10.155.

- ↑ For flaming hair of Agni and Bhairava see: Sivaramamurti, p. 11.

- ↑ Doniger, Wendy (1973). "The Vedic Antecedents". Śiva, the erotic ascetic. Oxford University Press US. pp. 84–9.

- ↑ For text of RV 2.20.3a as स नो युवेन्द्रो जोहूत्रः सखा शिवो नरामस्तु पाता । and translation as "May that young adorable Indra, ever be the friend, the benefactor, and protector of us, his worshipper" see: Arya & Joshi (2001), p. 48, volume 2.

- ↑ For text of RV 6.45.17 as यो गृणतामिदासिथापिरूती शिवः सखा । स त्वं न इन्द्र मृलय ॥ and translation as "Indra, who has ever been the friend of those who praise you, and the insurer of their happiness by your protection, grant us felicity" see: Arya & Joshi (2001), p. 91, volume 3.

- ↑ For translation of RV 6.45.17 as "Thou who hast been the singers' Friend, a Friend auspicious with thine aid, As such, O Indra, favour us" see: Griffith 1973, p. 310.

- ↑ For text of RV 8.93.3 as स न इन्द्रः सिवः सखाश्चावद् गोमद्यवमत् । उरूधारेव दोहते ॥ and translation as "May Indra, our auspicious friend, milk for us, like a richly-streaming (cow), wealth of horses, kine, and barley" see: Arya & Joshi (2001), p. 48, volume 2.

- ↑ For the bull parallel between Indra and Rudra see: Chakravarti, p. 89.

- ↑ RV 7.19.

- ↑ For the lack of warlike connections and difference between Indra and Rudra, see: Chakravarti, p. 8.

- ↑ For Shiva as depicted with a third eye, and mention of the story of the destruction of Kama with it, see: Flood (1996), p. 151.

- ↑ For a review of theories about the meaning of tryambaka, see: Chakravarti, pp.37-39.

- ↑ For usage of the word ambaka in classical Sanskrit and connection to the Mahabharata depiction, see: Chakravarti, pp. 38-39.

- ↑ For translation of Tryambakam as "having three mothers" and as an epithet of Rudra, see: Kramrisch, p. 483.

- ↑ For vedic Sanskrit meaning and "having three mothers" as the translation of Max Müller and Macdonell, see: Chakravarti, pp. 37-38.

- ↑ For discussion of the problems in translation of this name, and the hypothesis regarding the Ambikās see: Hopkins (1968), p. 220.

- ↑ For the Ambikā variant, see: Chakravarti, pp. 17, 37.

- ↑ For the moon on the forehead see: Chakravarti, p. 109.

- ↑ For śekhara as crest or crown, see: Apte, p. 926.

- ↑ For Chandraśekhara as an iconographic form, see: Sivaramamurti (1976), p. 56.

- ↑ For translation "Having the moon as his crest" see: Kramrisch, p. 472.

- ↑ For the moon iconography as marking the rise of Rudra-Shiva, see: Chakravarti, p. 58.

- ↑ For discussion of the linkages between Soma, Moon, and Rudra, and citation to RV 7.74, see: Chakravarti, pp. 57-58.

- ↑ 78.0 78.1 78.2 78.3 Flood (1996), p. 151.

- ↑ Flood (1996), pp. 92, 161.

- ↑ Flood (1996), p. 161.

- ↑ Chidbhavananda, p. 23.

- ↑ Chidbhavananda, p. 22.

- ↑ For translation of Kapardin as "Endowed with matted hair" see: Sharma 1996, p. 279.

- ↑ Kramrisch, p. 475.

- ↑ For Kapardin as a name of Shiva, and description of the kaparda hair style, see, Macdonell, p. 62.

- ↑ Sharma 1996, p. 290

- ↑ See: name #93 in Chidbhavananda, p. 31.

- ↑ For Shiva drinking the poison churned from the world ocean see: Flood (1996), p. 78.

- ↑ 89.0 89.1 Kramrisch, p. 473.

- ↑ Ziegenbalg, Bartholomaeus; Germann ,Wilhelm and Metzger, G.J. (869). Genealogy of the South-Indian Gods. Germann1. p. 151.

- ↑ For alternate stories about this feature, and use of the name Gaṅgādhara see: Chakravarti, pp. 59 and 109.

- ↑ For description of the Gaṅgādhara form, see: Sivaramamurti (1976), p. 8.

- ↑ For Shiva supporting Gaṅgā upon his head, see: Kramrisch, p. 473.

- ↑ "Mythology ~ The birth of Brahmarishis". http://www.tamilstar.com/mythology/brahmarishis. Retrieved 2008-05-07.

- ↑ Flood (1996), p. 151

- ↑ Michaels, p. 218.

- ↑ For definition and shape, see: Apte, p. 461.

- ↑ Jansen, p. 44.

- ↑ Jansen, p. 25.

- ↑ For use by Kāpālikas, see: Apte, p. 461.

- ↑ For a review of issues related to the evolution of the bull (Nandin) as Shiva's mount, see: Chakravarti, pp. 99-105.

- ↑ For spelling of alternate proper names Nandī and Nandin see: Stutley, p. 98.

- ↑ Sharma 1996, p. 291

- ↑ Kramrisch, p. 479.

- ↑ Dictionary of Hindu Lore and Legend (ISBN 0-500-51088-1) by Anna L. Dallapiccola

- ↑ For identification of Mount Kailāsa as the central linga, see: Stutley (1985), p. 62.

- ↑ Keay, p. 33.

- ↑ For quotation "Śiva is a god of ambiguity and paradox" and overview of conflicting attributes see: Flood (1996), p. 150.

- ↑ For quotation regarding Yajur Veda as containing contrary sets of attributes, and marking point for emergence of all basic elements of later sect forms, see: Chakravarti, p. 7.

- ↑ For summary of Shiva's contrasting depictions in the Mahabharata, see: Sharma 1988, p. 20-21.

- ↑ For rud- meaning "cry, howl" as a traditional etymology see: Kramrisch, p. 5.

- ↑ Citation to M. Mayrhofer, Concise Etymological Sanskrit Dictionary, s.v. "rudra", is provided in: Kramrisch, p. 5.

- ↑ Sharma 1996, p. 301.

- ↑ Sharma 1996, p. 314.

- ↑ For translation of Mahākāla as "Time beyond time" see: Kramrisch, p. 476.

- ↑ For the name Kāla translated as "time; death", see: Kramrisch, p. 474.

- ↑ The name Kāla appears in the Shiva Sahasranama, where it is translated by Ram Karan Sharma as "(The Supreme Lord of) Time". See: Sharma 1996, p. 280.

- ↑ For भैरव as one of the eight forms of Shiva, and translation of the adjectival form as "terrible" or "frightful" see: Apte, p. 727, left column.

- ↑ For Bhairava form as associated with terror see: Kramrisch, p. 471.

- ↑ Kramrisch, p. 481.

- ↑ For adoption of the name Śaṇkara by Shankaracarya see: Kramrisch, p. 481.

- ↑ For dating Shankaracharya as 788-820 CE see: Flood (1996), p. 92.

- ↑ For translation of Śambhu as "Causing Happiness" see: Kramrisch, p. 481.

- ↑ For speculation on the possible etymology of this name, see: Chakravarti, pp. 28 (note 7), and p. 177.

- ↑ For the contrast between ascetic and householder depictions, see: Flood (1996), pp. 150-151.

- ↑ For Shiva's representation as a yogin, see: Chakravarti, p. 32.

- ↑ For name Mahāyogi and associations with yoga, see, Chakravarti, pp. 23, 32, 150.

- ↑ For the ascetic yogin form as reflecting Epic period influences, see: Chakravarti, p. 32.

- ↑ For Umāpati, Umākānta and Umādhava as names in the Shiva Sahasranama literature, see: Sharma 1996, p. 278.

- ↑ For Umā as the oldest name, and variants including Pārvatī, see: Chakravarti, p. 40.

- ↑ For Pārvatī identified as the wife of Shiva, see: Kramrisch, p. 479.

- ↑ For regional name variants of Karttikeya see: Gupta, Preface.

- ↑ 133.0 133.1 Search for Meaning By Antonio R. Gualtieri

- ↑ For description of the nataraja form see: Jansen, pp. 110-111.

- ↑ For interpretation of the naṭarāja form see: Zimmer, pp. 151-157.

- ↑ For names Nartaka (Sanskrit नर्तक) and Nityanarta (Sanskrit नित्यनर्त) as names of Shiva, see: Sharma 1996, p. 289.

- ↑ For prominence of these associations in puranic times, see: Chakravarti, p. 62.

- ↑ For popularity of the nṛtyamūrti and prevalence in South India, see: Chakravarti, p. 63.

- ↑ Kramrisch, Stella (1994). "Siva's Dance". The Presence of Siva. Princeton University Press. p. 439.

- ↑ Klostermaier, Klaus K.. "Shiva the Dancer". Mythologies and Philosophies of Salvation in the Theistic Traditions of India. Wilfrid Laurier Univ. Press. p. 151.

- ↑ Massey, Reginald. "India's Kathak Dance". India's Kathak Dance, Past Present, Future. Abhinav Publications. p. 8.

- ↑ 142.0 142.1 Moorthy, Vijaya (2001). Romance of the Raga. Abhinav Publications. p. 96.

- ↑ Leeming, David Adams (2001). A Dictionary of Asian Mythology. Oxford University Press. p. 45.

- ↑ Radha, Sivananda (1992). "Mantra of Muladhara Chakra". Kuṇḍalinī Yoga. Motilal Banarsidass. p. 304.

- ↑ For iconographic description of the Dakṣiṇāmūrti form, see: Sivaramamurti (1976), p. 47.

- ↑ For description of the form as representing teaching functions, see: Kramrisch, p. 472.

- ↑ For characterization of Dakṣiṇāmūrti as a mostly south Indian form, see: Chakravarti, p. 62.

- ↑ For the deer-throne and the audience of sages as Dakṣiṇāmūrti, see: Chakravarti, p. 155.

- ↑ Goldberg specifically rejects the translation by Frederique Marglin (1989) as "half-man, half-woman", and instead adopts the translation by Marglin as "the lord who is half woman" as given in Marglin (1989, 216). Goldberg, p. 1.

- ↑ For evolution of this story from early sources to the epic period, when it was used to enhance Shiva's increasing influence, see: Chakravarti, p.46.

- ↑ For the Tripurāntaka form, see: Sivaramamurti (1976), pp. 34, 49.

- ↑ Flood (1996), p. 29.

- ↑ Tattwanandaz, pp. 49-52.

- ↑ 154.0 154.1 154.2 Harshananda, Swami. "Sivalinga". Principal Symbols of World Religions. Sri Ramakrishna Math Mylapore. pp. 6–8.

- ↑ See Monier William's Sanskrit to english Dictionary

- ↑ O'Flaherty, Wendy Doniger (1981). Śiva, the erotic ascetic. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-520250-3.

- ↑ Isherwood, Christopher. "Early days at Dakshineswar". Ramakrishna and his disciples. p. 48.

- ↑ Sen, Amiya P. (2006). "Editor's Introduction". The Indispensable Vivekananda. Orient Blackswan. pp. 25–26.

- ↑ Sivananda, Swami (1996). "Worship of Siva Linga". Lord Siva and His Worship. The Divine Life Trust Society. http://www.dlshq.org/download/lordsiva.htm#_VPID_80.

- ↑ Balagangadhara, S.N.; Sarah Claerhout (Spring 2008). "Are Dialogues Antidotes to Violence? Two Recent Examples From Hinduism Studies". Journal for the Study of Religions and Ideologies 7 (19): 118–143. http://www.jsri.ro/new/?download=19_balagangadhara_claerhout.pdf.

- ↑ Harding, Elizabeth U. (1998). "God, the Father". Kali: The Black Goddess of Dakshineswar. Motilal Banarsidass. pp. 156–157. ISBN 9788120814509.

- ↑ 162.0 162.1 Vivekananda, Swami. "The Paris congres of the history of religions". The Complete Works of Swami Vivekananda. Vol.4. http://www.ramakrishnavivekananda.info/vivekananda/volume_4/translation_prose/the_paris_congress.htm.

- ↑ Parrinder, Edward Geoffrey (1982). Avatar and incarnation. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 88. ISBN 0-19-520361-5.

- ↑ Padma Purana 6.236.7-11

- ↑ Sri Ramakrishna Math (1985) "Hanuman Chalisa" p. 5

- ↑ Mani, Vettam (1975). Puranic Encyclopaedia: A Comprehensive Dictionary With Special Reference to the Epic and Puranic Literature. Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass. p. 859. ISBN 0842-60822-2.

- ↑ For five as a sacred number, see: Kramrisch, p. 182.

- ↑ It is first encountered in an almost identical form in the Rudram. For the five syllable mantra see: Kramrisch, p. 182.

- ↑ For discussion of these five forms and a table summarizing the associations of these five mantras see: Kramrisch, pp. 182-189.

- ↑ For distinct iconography, see Kramrisch, p. 185.

- ↑ For association with the five faces and other groups of five, see: Kramrisch, p. 182.

- ↑ For the epithets pañcamukha and pañcavaktra, both of which mean "five faces", as epithets of Śiva, see: Apte, p. 578, middle column.

- ↑ For variation in attributions among texts, see: Kramrisch, p. 187.

- ↑ Kramrisch, p. 184.

- ↑ Quotation from Pañcabrahma Upanishad 31 is from: Kramrisch, p. 182.

- ↑ For relatively minor position in Vedic times, and rise in progress by 1000-700 BCE see: Zimmer (1946), p. 125, note 2.

- ↑ For the rise in popularity of Shiva and Vishnu, and the role of Puranas in promoting sectarian positions, see: Flood (1996), pp. 110-111.

- ↑ For Visnu becoming Shiva in Vaishnava myths, see: Zimmer (1946), p. 125.

- ↑ For Vishnu Purana dating of 4th c. CE and role of Vishnu as supreme deity, see: Flood (1996), p. 111.

- ↑ For identification of Shiva as a manifestation of Vishnu see: Bhagavata Purana 4.30.23, 5.17.22-23, 10.14.19.

- ↑ For predominant role of Shiva in some myths, see: Zimmer (1946), p. 128.

- ↑ For the lingodbhava myth, and Vishnu and Brahmā as emanations of Shiva, see: Zimmer (1946), pp. 128-129.

- ↑ For translation of the epithet शिपिविष्ट (IAST: śipiviṣṭa) as "salutation to him of the form of Vishṇu" included in the fifth anuvāka, and comment that this epithet "links Śiva with Vishṇu" see: Sivaramamurti, pp. 21, 64.

- ↑ For Śarabha as an "animal symplegma" form of Shiva, see: Kramrisch, p. 481.

- ↑ For incarnation in composite form as man, bird, and beast to chastise Narasimha, see: Chakravarti, p. 49.

- ↑ Sharma, B. N. Krishnamurti (2000). A history of the Dvaita school of Vedānta and its literature: from the earliest beginnings to our own times. Motilal Banarsidass Publ.. p. 412. ISBN 9788120815759. http://books.google.com/?id=FVtpFMPMulcC&pg=PA412.

- ↑ Chakravarti, pp. 54-55.

- ↑ For Harirudra citation to Mbh. III.39.76f see: Hopkins (1969), p. 221.

- ↑ For the story of Rāvaṇa and the Mahābaleśvara linga see: Chakravarti, p. 168.

- ↑ Doniger, Wendy (1999). Splitting the difference: gender and myth in ancient Greece and India. London: University of Chicago Press. pp. 263–5. ISBN 9780226156415. http://books.google.com/?id=JZ8qfQbEJB4C&pg=PA263&dq=mohini+Vishnu&cd=2#v=onepage&q=mohini%20Vishnu.

- ↑ Vanita, Ruth; Kidwai, Saleem (2001). Same-sex love in India: readings from literature and history. Palgrave Macmillan. p. 69. ISBN 9780312293246.

- ↑ Pattanaik, Devdutt (2001). The man who was a woman and other queer tales of Hindu lore. Routledge. p. 71. ISBN 9781560231813. http://books.google.com/?id=Odsk9xfOp6oC&pg=PA71&dq=mohini&cd=2#v=onepage&q=mohini.

- ↑ See Mohini#Relationship_with_Shiva for details

- ↑ Lord Shiva. Diamond Pocket Books Pvt. Ltd.. 2001. p. 49. ISBN 81-7182-686-5. http://books.google.com/?id=Lkqf5GrupR8C&pg=PA44&dq=shivaratri&q=shivaratri.

- ↑ "Newly constructed Shiva's statue in Bijapur is next to Murudeshwar statue". The Hindu. 2006-01-23. http://www.hindu.com/2006/01/23/stories/2006012304670300.htm. Retrieved 2010-06-06.

References

- Apte, Vaman Shivram (1965). The Practical Sanskrit Dictionary (Fourth revised and enlarged ed.). Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass Publishers. ISBN 81-208-0567-4

- Arya, Ravi Prakash & K. L. Joshi. Ṛgveda Saṃhitā: Sanskrit Text, English Translation. Parimal Publications, Delhi, 2001, ISBN 81-7110-138-7 (Set of four volumes). Parimal Sanskrit Series No. 45; 2003 reprint: 81-7020-070-9.

- Chakravarti, Mahadev (1994). The Concept of Rudra-Śiva Through The Ages (Second Revised ed.). Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass. ISBN 81-208-0053-2

- Chidbhavananda, Swami (1997). Siva Sahasranama Stotram: With Navavali, Introduction, and English Rendering. Sri Ramakrishna Tapovanam. ISBN 81-208-0567-4. (Third edition). The version provided by Chidbhavananda is from chapter 17 of the Anuśāsana Parva of the Mahābharata.

- Courtright, Paul B. (1985). Gaṇeśa: Lord of Obstacles, Lord of Beginnings. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN ISBN 0-19-505742-2.

- Flood, Gavin (1996). An Introduction to Hinduism. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-43878-0.

- Flood, Gavin (Editor) (2003). The Blackwell Companion to Hinduism. Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishing. ISBN 1-4051-3251-5.

- Goldberg, Ellen (2002). The Lord Who is Half Woman: Ardhanārīśvara in Indian and Feminist Perspective. Albany, New York: State University of New York Press. ISBN 0-7914-5326-X.

- Griffith, T. H. (1973). The Hymns of the Ṛgveda (New Revised ed.). Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass. ISBN 81-208-0046-X

- Gupta, Shakti M. (1988). Karttikeya: The Son of Shiva. Bombay: Somaiya Publications Pvt. Ltd.. ISBN 81-7039-186-5.

- Hopkins, E. Washburn (1969). Epic Mythology. New York: Biblo and Tannen. Originally published in 1915.

- Jansen, Eva Rudy (1993). The Book of Hindu Imagery. Havelte, Holland: Binkey Kok Publications BV. ISBN 90-74597-07-6.

- Keay, John (2000). India: A History. New York: Grove Press. ISBN 0-8021-3797-0.

- Kramrisch, Stella (1981). The Presence of Śiva. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press. ISBN 0-691-01930-4.

- Macdonell, Arthur Anthony (1996). A Practical Sanskrit Dictionary. New Delhi: Munshiram Manoharlal Publishers. ISBN 81-215-0715-4.

- Mate, M. S. (1988). Temples and Legends of Maharashtra. Bombay: Bharatiya Vidya Bhavan.

- Michaels, Axel (2004). Hinduism: Past and Present. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press. ISBN 0-691-08953-1.

- Sarup, Lakshman (1920-1927). The Nighaṇṭu and The Nirukta. Reprint: Motilal Banarsidass, 2002, ISBN 81-208-1381-2.

- Sharma, Ram Karan (1988). Elements of Poetry in the Mahābhārata (Second ed.). Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass. ISBN 81-208-0544-5

- Sharma, Ram Karan (1996). Śivasahasranāmāṣṭakam: Eight Collections of Hymns Containing One Thousand and Eight Names of Śiva. Delhi: Nag Publishers. ISBN 81-7081-350-6 This work compares eight versions of the Śivasahasranāmāstotra with comparative analysis and Śivasahasranāmākoṣa (A Dictionary of Names). The text of the eight versions is given in Sanskrit.

- Sivaramamurti, C. (1976). Śatarudrīya: Vibhūti of Śiva's Iconography. Delhi: Abhinav Publications.

- Stutley, Margaret (1985). The Illustrated Dictionary of Hindu Iconography. First Indian Edition: Munshiram Manoharlal, 2003, ISBN 81-215-1087-2.

- Tattwananda, Swami (1984). Vaisnava Sects, Saiva Sects, Mother Worship. Calcutta: Firma KLM Private Ltd.. First revised edition.

- Zimmer, Heinrich (1946). Myths and Symbols in Indian Art and Civilization. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press. ISBN 0-691-01778-6. First Princeton-Bollingen printing, 1972.

- Hanuman Chalisa. Chennai, India: Sri Ramakrishna Math. 1985. ISBN 81-7120-086-9.

|

|||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||

|

|||||||